[This is an epically long post – over 3000 words – it ought to be at least two or three posts, but I’m far too busy writing a PhD to give this the kind of attention it needs and deserves in terms of editing, tidying and whatnot. So make of it what you will… that said, it may be helpful if you’re trying to get your head round the various arguments about Spotify]

With the recent increased scrutiny placed on Spotify thanks to their tendency to give millions of dollars to berks who give a platform to conspiracy theorists and transphobes, it has also amongst my musician friends reignited the discussion about Spotify’s economics. Something on which I’ve been pretty vocal over time. So I’m going to try and summarise that here, and then offer some thoughts on streaming and why the argument against Spotify is not an argument against streaming. And therefor why I hope that any collapse in Spotify’s position in the market (it’s WAY too early to make that call, but we can hope, right?) would possibly offer us a chance to rethink the economics of streaming.

So, Spotify’s problems, summarised – Spotify began by realising that they needed two things to get an edge over everyone else in the race to be the first ‘all you can eat’ streaming service – a catalogue and a platform. The catalogue they kickstarted by doing equity deals with the Major labels and the platform they got (I can’t find the reference for how this worked, but I definitely remember it being talked about at the time!) by – I think – doing a deal with 7 Digital who built the first version of Spotify in exchange for the being the exclusive ‘shop’ within Spotify – yup, when Spotify first started, you could buy most of the music that they played inside the browser window. So the idea that Spotify pointed you to a sales opportunity and had no mobile app made it a very different proposition with a very different set of affordances. At that point, the ‘Spotify is more like radio’ argument was a whole lot more compelling that it is now. Which is not to say that there aren’t millions of Spotify users who use it like radio, just that the number of prior experiences and economic transactions that it has subsumed is way, way more complex than it was in Year 1. (it’s worth noting that Spotify weren’t the first to try the same thing – an almost identical app called Datz was built, and had a press launch but it turned out their attempts to get the majors on side involved a whole lot of lying to each of their negotiators who rather awkwardly actually talked to each other ahead of the launch, and the whole thing collapsed spectacularly).

As Spotify evolved into some kind of ‘total music solution’, removing the sales platform not long after the deal with 7 Digital ran out, and adding a mobile app and offline storage as soon as they could, their economic model (which made sense in relation to radio, but was problematic in terms of cannibalising sales revenue) didn’t evolve. It just got more opaque. News emerged of bands and territories and labels negotiating different deals, of Spotify lobbying to reduce statutory royalty payments for streams, and despite having been to at least three talks where it was explained in depth, I still couldn’t tell you in any great detail how Spotify calculates who gets what. However, there were winners – it became a new form of ‘viral’ success to have a playlist hit, one track that landed on a massively subscribed playlist and made good money for the artist. What was also apparent, perhaps like radio in this respect, was that there was minimal lateral movement from playlists to wider awareness of the artist. Spotify itself didn’t really engender that kind of audience building.

Which brings us to the problem of communication – Spotify for a long time gave no analytic detail to artists. Following a campaign by, amongst others, Cellist Zoë Keating, they eventually made some available, but it still wasn’t all that easy to access depending on which aggregator you used to get your music on the platform, and there was still no way to converse with your audience. That aspect of fan/audience/community building has always remained well out of reach of the platform itself. There were many stories of artists leveraging Spotify to build audiences, and for those who owned their entire catalogue and publishing, the economics were in some cases quite reasonable.

However, the simple fact remained that the purpose of Spotify, economically speaking, was built around the re-leveraging of IP/value in existing catalogue. Getting people to pay again to listen to works they’d already bought. For the Major labels, almost all the value they have is in music we already love. They are looking at a humungous volume of songs and albums that we already love, that have already made, collectively, billions of dollars in sales and royalties, that have been milked via reissues, reformatting and remastering for decades, that can now without any manufacturing at all, be turned into a steady trickle of income that collectively amounts to a hell of a lot of money, especially if you have equity in the company, get a preferential royalty rate AND a shareholder payout. You get paid for your own work, and a cut of the profit on everyone else’s, as well as – I assume – a much deeper access to analytic detail across the entire economy.

So bands that had effectively made all their money and for the last couple of decades were making extra on licensing and CD reissues, suddenly had a way of not only reselling, but monetising usage. Experience pricing is what it’s called in some circles. You’re not paying for a product, you’re paying to access an experience. Paying by the amount of time (or, crucially, the number of times) you access a particular piece or song. It’s notable that Spotify pay per play, not by minute of play – this has both increased the number of tracks on an ‘average’ album considerably, and shortened the length of pop songs too. Affordances, eh?

So, there’s essentially no meaningful way to contact your listening audience on Spotify, the money only works at scale, in an economic model that was designed to leverage back catalogue value not recoup recording and marketing budgets, the calculations were opaque and favoured the majors (meet the new boss, same as the old, coked-up, wanker boss) and throw in a few scandals around fake artists and arms dealing and you’ve got yourself one toxic fucking stew of wholly untenable ethical wrongness. Except because of the deals with labels, many, many artists were unable to extract their catalogue, and because of the near-monopoly Spotify had on the conversation around streaming (if not the entire market – they’re the biggest player, but Apple, Amazon and to a lesser extent Tidal have a chunk too, as well as some other smaller players) a lot of artists were terrified to pull out and were in no position to actually talk honestly with their audience about what was going on and why the economic model was potentially ruinous for their creative endeavours.

As someone who was in control of my entire audience, who knew virality was a ridiculously long shot, didn’t want to make music designed for playlists and NEEDS to talk to his audience, I pulled my music off Spotify almost exactly a decade ago – the basic argument is a fair trade one – the company sucks in every imaginable way, and I didn’t need to have anything to do with it. I also pulled all my music of Amazon and a host of other platforms, and have refused to use either service for the same amount of time.

But, alongside that has been an ever increasing level of frustration with the nature of the argument against Spotify and the way that it becomes a bunch of essentialist garbage about ‘streaming’. I’ve almost certainly stumbled into this particular mess myself on more than one occasion. So let’s talk about streaming.

Spotify’s model uses streaming as its technological foundation, but Spotify is not synonymous with streaming. Streaming at its most basic just means that the file that is being decoded into music is hosted elsewhere. That’s all. To that extent, Bandcamp is also a streaming service – the fact that most of my Bandcamp listening happens through either the web browser or the mobile app is made possible by Bandcamp’s essential nature as being in part a streaming service. That streaming in no way undermines their economic model, in fact it’s pretty integral to it given how easily it makes accessing the deeper recesses of your Bandcamp collection, as well as browsing other new work with a view to buying it.

Where Bandcamp and Spotify diverge in their use of streaming is the economic model around that streaming. On Bandcamp, the music that I’m streaming is either free for me to hear because the band or small label have made it so I can hear it, or it’s music that I’ve bought and I own. And by own I mean it’s mine to access and play over and over again for as long as I want without paying any more money to keep accessing it. I can download the file in as many different formats as I want, play them on any device without interference, and the amount I paid for it in the first place is the only exchange of money needed for that to continue.

In contrast, Spotify sells two things – first of all it rents access to the catalogue – you can either pay for that with time by listening to adverts, or you can pay to remove those ads and have access to it all for a monthly fee. That money you pay doesn’t go directly to whoever you listen to, but it goes into the central pot of Spotify earnings that is then divvied up amongst the rights holders, with the Majors getting their bit first and everyone else getting theirs based on a pecking order and the percentage of the total Spotify streams that their work represents.

What you also get for your money is a cloud of metadata built up around you and your listening habits. Some of it you control –

- playlists,

- bookmarks,

- previously listened to work,

- stuff you’ve favourited,

- curated playlists that you’re subscribed to

and a load that you have less direct control over –

- the content of those curated playlists,

- other data scraped from your social media profiles and traded for the targeting of ads or music promo,

- the ways in which Spotify maps your music community and includes their preferences in what it recommends you listen to,

- and people just buying access to your ears in various ways.

These are all variously super useful or annoying depending on how well you perceive their algorithms to work at finding your taste, and how comfortable you are with their particular way of cataloging and bookmarking the work that feels like your collection.

If you stop paying, or suddenly get super tired of listening to ads and decide to delete your account, your access is gone. No matter how much you’ve previously paid, you no longer have access to that music. You are only ever renting access to that music, and there’s no point at which you have paid ‘enough’. No point at which it becomes yours beyond the walls of the service. There are myriad unlicensed ways of extracting music from Spotify, easiest being just recording the music as it plays into a DAW, but there’s absolutely no way of taking your catalogue of work elsewhere or even transferring the metadata in any useful way. (it’s worth artists being a little more aware of this when they get frustrated at people not quitting Spotify soon enough – it’s a big break to drop all of that metadata and start again elsewhere, especially if it’s a completely different economic model you’re suggesting!)

So what you’re paying for is no longer about ownership of music. It’s about experiencing music, and you pay based on what you listen to.

It’s super important to realise how hard – impossible, even – it is to usefully compare these two ways of paying for music in the short term. So much of the commentary around the economics of Spotify fails to understand who is massively advantaged in experience pricing and how much of the way we’ve always listened to music is now suddenly economically active as well as generating highly valuable metadata, in ways it has never been before. The reasons for this I’ve already explained. But what’s also ignored is how the fact that people who keep listening keep paying you impacts the longer term economics of any given track or album.

So what’s the big deal? The experience economy surely extends the economic lifespan of recorded music way beyond the extremely short shelf-life of the vast majority of music under the old system (especially when we factor in just how epically limited shelf-space was in record shops before digitsiation made it possible to access the vast majority of the history of recorded music via some means or other).

The problems for me are as follows. The first one is Spotify’s expressed and repeated action that demonstrates a desire to pay as little as is humanly possible for the rights to music. There’s no ‘how much do we need to comfortably run this service while still making the lives of musicians better?’ – the basic economics is transnational capitalism as its most fucked up, with opaque bilateral deals, lobbying and a bunch of shit that’s basically fraudulent, before we even get to the justification for giving $100M to fucking Joe Rogan to spout bullshit.

So their payment system, which works for the Majors as a way of leveraging extra money on music that people already love, makes it exceedingly difficult to justify the even modest recording and promotional budgets on which the vast majority of indie music industry machinery is built. Let’s not kid ourselves that being an indie musician has ever been easy, or a place where you’re likely to do well. But in an economic field where there are myriad ways of funnelling money into the pockets of those most in need of it, Spotify fails. If your response to this is ‘ah well, that’s how capitalism works’, then I wish you all the ill-effects capitalism has to offer. I want better than that for the world, so it’s a piss-poor excuse.

Secondly, in order to keep you wedded to their ecosystem and keep you paying, Spotify stays as an intermediary between you and your audience, making direct communication super difficult, and/or expensive. Sure you can take out ads and target your previous listeners, but there’s no reason that should be the case in a service that’s already made billions out of your work being on there. Again, capitalism isn’t a good enough excuse for shitting on broke musicians.

Thirdly, absolutely no thought has been given to how communities form around music beyond the aggregating of massive listening data. Which works to connect you with more music in the system, but it doesn’t allow human relationships to cross-over into relationships of mutual discovery. The trust relationship Spotify is built to enhance is our trust in its recommendation engine, not our trust in each other to find and talk about music, and certainly not our trust as artists in our audience to do that. This isn’t an even vague part of Spotify’s remit, but from where I am, fostering human relationships based on care, conversation, trust and accumulated experience and wisdom is vital to every context in which I’ve ever found out about music, from hanging out with friends through to what I learn from my own subscribers on Bandcamp.

So how does this reflect on streaming? It doesn’t. There’s nothing inherently bad about streaming. There are streaming services that pay masses more than Spotify does. There are other possible economic models that make experience pricing way more meaningful and viable, and there are ways to enable fan communities to function as communities rather than an algorithm-generated blob of metadata.

There are experiments with new ways of doing this that are worth looking at – Resonate, while not actually functioning in a way that I find useful yet, is a cool and helpful way of thinking about fair trade experience pricing and the transition to ownership. At least one of the bigger streaming companies has suggested it will switch to a model of dividing up what you pay to the people you listen to – no more communal pot to pay for the free/ad streams out of other people’s paid accounts. FairMus seems to be an experiment in this model – it seems like a supremely obvious one to me – I can’t see any decent reason why this wouldn’t be the model from the off, but it’s another reason to hate Spotify. I have no desire for my subscription money to go to making rich people more rich while the broke-ass band I’ve listened to for three hours this week only gets pennies.

I have no innate problem with experience pricing – as a man of a certain age, I am still a fan of ownership, I like the long term implications of buying things on Bandcamp and being able to download them, them being mine, but that’s a cultural thing, not an ethical one. Ownership doesn’t really matter, and I love the fact that experience pricing makes it possible to get paid for people loving your music more. It’s not true at all that the more you pay for something the more you love it – that’s another weird myth that’s totally undone by the number of favourite albums I and many other have that we bought for 50p in a discount bin – but it does make sense that the opposite is possible, that my money is somehow divided up amongst the people I listen to most.

But that’s not the whole picture. There are artists whose music I barely listen to who I still want to give money to for their work. Not by ‘tipping’ them but by buying their work. I actually really enjoy being able to encourage people who make interesting work to keep doing it even when it’s not what I am in a position to listen to all day long. I don’t think that the estates of Miles Davis or Jimi Hendrix or The Beatles need any more money from me no matter how much time I spent listening to them. With a product-based economy, I’m continually investing in new work, and I can do it at the point of departure for a project, and it’s not spread out over the next few years. So the economic return is front-loaded, but may actually end up being smaller in the long term than via a fairer trade experience pricing model.

So maybe what we need is both. I know a LOT of people who have told me over the years that they use streaming services to predominantly play music they already own. This points to the inherent conservatism of older people’s music taste – genuine new music foragers above the age of maybe 25 are fairly rare as far as I can see. They are a significant chunk of the music buying market, because they have disposable income, but the majority of their peers are spending their money on vinyl reissues or Sonos systems, not investing in new artists. I’m not one to put much extra weight on what ‘the mainstream’ does, simply because it’s never been a place where epically creative work has been the norm, and while it did for years sustain a middle class of performing musicians who are struggling today, that’s as much about the cost of living and the significant relative drop in the cultural standing and meaning of music against other forms of entertainment as it is any internal collapse in the music industry. If you want to campaign for musicians to live better, your energies are probably best used arguing for rent control and UBI rather than railing against the significantly less impactful internal economic squabbles of the music industry.

So streaming is OK with me, Spotify very much isn’t. Should you use another streaming service? I’ve not yet seen one that interests me as a listener, but I’m really not sure what I’ll do the next time I want to buy an album that isn’t on Bandcamp – I used to shop on Google Play, but as I won’t shop on Amazon and iTunes is a giant ball-ache to use, I’m not sure where I’ll go. It’s getting harder and harder to just buy non-Bandcamp music for a sensible amount. We’ll see where that goes.

If you’ve made it this far, well done – email me and I’ll send you a download code for something lovely on Bandcamp.

Having discovered an amazing plug-in by Baby Audio called Smooth Operator, I recently realised that my mix/mastering process for the last couple of years of releases was underselling a lot of the detail in the recordings. The more muted, introspective tone of the releases made some sense in the context of the Pandemic followed by a year of Cancer related shenanigans, but didn’t represent the music to its fullest extent. So I’ve set about remastering my most recent public albums first, and have now uploaded Time Stops vols 1-3 (vol 3 is Bandcamp subscriber-only).

Having discovered an amazing plug-in by Baby Audio called Smooth Operator, I recently realised that my mix/mastering process for the last couple of years of releases was underselling a lot of the detail in the recordings. The more muted, introspective tone of the releases made some sense in the context of the Pandemic followed by a year of Cancer related shenanigans, but didn’t represent the music to its fullest extent. So I’ve set about remastering my most recent public albums first, and have now uploaded Time Stops vols 1-3 (vol 3 is Bandcamp subscriber-only). The remasters are uploaded in place of the original albums, so if you’ve already bought the albums, you don’t need to pay for them again to get the new versions. If you downloaded them originally when you bought them or got them through the subscription, you’re most welcome to download them again and compare the two. If you make music yourself, it might be instructive to do so!

The remasters are uploaded in place of the original albums, so if you’ve already bought the albums, you don’t need to pay for them again to get the new versions. If you downloaded them originally when you bought them or got them through the subscription, you’re most welcome to download them again and compare the two. If you make music yourself, it might be instructive to do so!

But first a couple of thoughts on why one to one lessons are the right choice for many musicians. Coming out of the summer and re-entering the academic year, a lot of people find themselves starting to think about their music learning and what can take it to the next level.

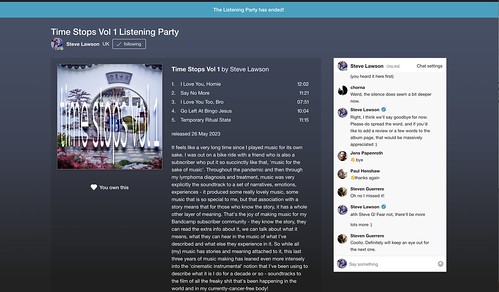

But first a couple of thoughts on why one to one lessons are the right choice for many musicians. Coming out of the summer and re-entering the academic year, a lot of people find themselves starting to think about their music learning and what can take it to the next level. For an artist as prolific as Steve Lawson, ‘new album’ can mean a lot of things. Time Stops, in Steve’s own words, marks the first time in a long way that the music hasn’t been catharsis-first. “It feels like a very long time since I played music for its own sake.” says Steve, going on to explain “Throughout the pandemic and then through my lymphoma diagnosis and treatment, music was very explicitly the soundtrack to a set of narratives, emotions, experiences – it produced some really lovely music, some music that is so special to me, but that association with a story means that for those who know the story, it has a whole other layer of meaning.”

For an artist as prolific as Steve Lawson, ‘new album’ can mean a lot of things. Time Stops, in Steve’s own words, marks the first time in a long way that the music hasn’t been catharsis-first. “It feels like a very long time since I played music for its own sake.” says Steve, going on to explain “Throughout the pandemic and then through my lymphoma diagnosis and treatment, music was very explicitly the soundtrack to a set of narratives, emotions, experiences – it produced some really lovely music, some music that is so special to me, but that association with a story means that for those who know the story, it has a whole other layer of meaning.” The new double album, Time Stops, marks a return to a more traditional model of music making. Of course, stories and emotions and meaning are woven deep into the music as always, but its primary purpose wasn’t to soundtrack a life-changing experience for the subscriber audience. “I was just relishing getting back to exploring the music in my head outside of catastrophe and life-changing events” explains Steve, “Those experiences are here too, particularly the lightness of much of the music reflecting the feeling of currently being in remission, possibly for good, but this wasn’t ‘let’s document with music how I feel about having cancer’.”

The new double album, Time Stops, marks a return to a more traditional model of music making. Of course, stories and emotions and meaning are woven deep into the music as always, but its primary purpose wasn’t to soundtrack a life-changing experience for the subscriber audience. “I was just relishing getting back to exploring the music in my head outside of catastrophe and life-changing events” explains Steve, “Those experiences are here too, particularly the lightness of much of the music reflecting the feeling of currently being in remission, possibly for good, but this wasn’t ‘let’s document with music how I feel about having cancer’.” Across the two albums, Steve draws on the latest iteration of his intricate and bafflingly complex sound-world. The album was recorded while in California, where Steve was visiting the NAMM Show for the first time since January 2020, immediately pre-pandemic. It features his Elrick SLC signature 6 string fretted bass throughout and all the sounds are from the MOD Audio DuoX – a multi-FX pedal that offers an unparalleled level of audio manipulation and experimentation. Central to all of the work is what Steve describes as “some of the best melodic inventiveness I’ve recorded in many, many years. Melody is always central to my music world, but during the soundtrack-experiments of the last few years, large scale ambient works became the dominant form. Here, tunes are back in the foreground, big time!”

Across the two albums, Steve draws on the latest iteration of his intricate and bafflingly complex sound-world. The album was recorded while in California, where Steve was visiting the NAMM Show for the first time since January 2020, immediately pre-pandemic. It features his Elrick SLC signature 6 string fretted bass throughout and all the sounds are from the MOD Audio DuoX – a multi-FX pedal that offers an unparalleled level of audio manipulation and experimentation. Central to all of the work is what Steve describes as “some of the best melodic inventiveness I’ve recorded in many, many years. Melody is always central to my music world, but during the soundtrack-experiments of the last few years, large scale ambient works became the dominant form. Here, tunes are back in the foreground, big time!”