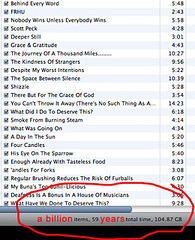

One of the big questions hanging over Spotify for me has been ‘do premium plays pay more than Spotify Lite plays?’ – I.E., do I get paid more if someone with a premium account plays my tunes vs. someone using the ad-funded version.

One of the big questions hanging over Spotify for me has been ‘do premium plays pay more than Spotify Lite plays?’ – I.E., do I get paid more if someone with a premium account plays my tunes vs. someone using the ad-funded version.

It stands to reason that the person with the premium account is paying more to listen, so surely you’d imagine that’d be reflected in the royalties?

At SXSW this year, the CEO of Spotify was giving a talk, I asked the question about royalty rates via Hugh Garry and apparently they are distributed evenly.

This is, as far as I can see, Spotify’s MASSIVE mistake. A deal-breaking, game-not-changing, screw-up of gargantuan proportions.

Here’s why.

The people best placed to promote Spotify are artists. We can link to it from our sites, we can provide links to it when we release new music, we can blog about how great it is and share music by our peers via the links.

If we push it, it becomes the place to find our music.

Spotify needs premium accounts for it to work. At the moment, their strategy for getting people signed up is to annoy the shit out of you with adverts until you capitulate. So you get irrelevant adverts that provide no value at all to the user, and therefor no value to the advertiser. Ergo, the amount paid per advert is likely to go down not up, killing the ad funded model. If I was an advertiser there’s no way I’d bother with Spotify. ‘Can you pay to produce an advert that we’re going to use to annoy people into paying not to hear it?’ no thanks.

So what would work? Spotify’s (and the other streaming services) best chance of success is if artists see it as a viable alternative to selling individual albums and tracks digitally. If it becomes that, the amount of traffic will go up and all that listening will be happening in a discovery environment, so more music will be heard by more people.

They could also make way more if the ads were something other than anti-value annoyances to be got rid of. There are loads of ways of making ads work in this setting – referrals, targeting, favouriting, user-profiles, profit-share, in-browser special offers… all kinds of stuff that would make the ad-side of the site self-supporting. If it isn’t currently viable, then the solution is to up the level of the ads even further til it is viable. The listener needs to FEEL what their listening is actually costing.

Why? Well, contrary to what Gerd Leonard has been telling us for years, ‘Feels Like Free’ is not the answer. It never has been and never will be. Free is, in fact, better than ‘feels like free’. I’d rather make my music free to download, no strings, and be rewarded in gratitude than have some weird filtered, taxation-based payment mechanism for it where people are left thinking music has neither cost nor value because there’s no tiered pricing, no opportunity to ‘pay what you like’, no thought about the value over and above the experience that access is via a portal and detached from the artist…

Listening to ads is a form of payment. We all know that. If the ads don’t cover it, then it’s a lie to keep that system going by subsidising those listens from people who are actually paying – people who are quite explicitly paying a subscription rate that puts a distinct value on their listening time. To not divide those up is to say that the value of both listens is the same. It isn’t.

- Spotify Lite is a limited but hugely useful discovery platform. If you have the kind of life where Spotify Lite is ‘enough’, then you weren’t about to pay £10 an album for CDs anyway. You’re probably the kind of person who listens to the radio and buys the occasional compilation. Certainly not the kind of person for whom £120 a year for Spotify premium is workable.

- Spotify Premium is an alternative to buying music. It’s also, when you look at how long people spend listening to music, a great model for paying a sensible amount per listen. If – and only if – it’s not being used to prop up a broken ad-funded ‘feels like free’ bullshit model.

If you want me to pay £10 a month for music, let me allocate where that £10 goes by choosing what I listen to. Make that £10 count, make it mean something. Cos otherwise, I’m going to stick with eMusic, where I know that my monthly sub goes to the people whose music I’m downloading. I know they get a set amount per track, that they wouldn’t get if I wasn’t paying for it. Real end to end value.

‘Til then, there’s no way on earth I’ll be paying for Spotify premium, and I won’t be encouraging anyone else to either.

If this feels like a deal-breaker to you, and you already have a premium account, you might want to consider cancelling it, and emailing Spotify to tell them why. Or better yet, blogging about why. Let’s have this discussion in public where possible.

[and before the inevitable ‘hey, I thought you loved Spotify!’ comments happen – I still think Spotify-lite is an awesome discovery tool. Spotify premium is, as yet, way too small a slice of anything to make me rethink my position on that. I don’t need to make money from Spotify-lite for its value to be realised. But the payment model that’s there doesn’t work, so the growth curve that Spotify needs to remain viable will be a seriously uphill struggle.]