[Warning: LONG read] I’ve just got back from a properly brilliant academic conference exploring Audience Research In The Arts – Audience research crosses a whole ton of disciplines and sub-disciplines, from sociology and anthropology to musicology and the science of memory. It was so invigorating to be around a massive group of people much smarter than me all trying to understand and illuminate different research angles on Audiences – who they are, what they do, how to reach them, the spaces they occupy and what those spaces mean, how they influence artists, and what kind of things they like, dislike and respond to… A dizzying array of magical goodness. If you want to see exactly what was on, here’s the conference program.

The main thing I brought away was a huge pile of methodological considerations that I now need to research and write up in the hope of getting back on track with my PhD, but there are a couple of things I want to think out loud about here. The first of them is this idea of creative freedom.

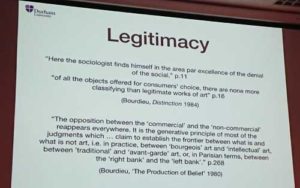

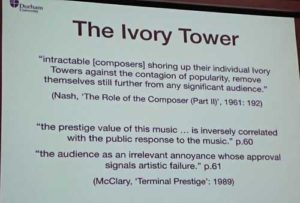

There was a really interesting paper given about contemporary composers and their variable perception of who their audience was and whether or not the only opinion that mattered was actually that of their peers. The starting point for it was this essay by Milton Babbitt that suggests normal‘ listeners aren’t sufficiently clever to understand the arcane workings of contemporary classical composition and that’s OK. The research project in question found a spread of opinion amongst the composers in its research data, but the bit that most intrigued me was the prevalence of uncritical takes on the concept of ‘creative freedom’ as an active state explicitly free from audience consideration. Given the many other research projects being presented that looked at imagined audiences, ad hoc audiences, that explored some of Bourdieu’s theories on how culture operates as an audience context for work created within that culture, and the 50 year history of reception studies acknowledging that even in broadcast media, the audience reception of a piece is an aspect of its production (creating a feedback loop), the uncritical lean towards the concept of artistic freedom seems particularly odd.

There was a really interesting paper given about contemporary composers and their variable perception of who their audience was and whether or not the only opinion that mattered was actually that of their peers. The starting point for it was this essay by Milton Babbitt that suggests normal‘ listeners aren’t sufficiently clever to understand the arcane workings of contemporary classical composition and that’s OK. The research project in question found a spread of opinion amongst the composers in its research data, but the bit that most intrigued me was the prevalence of uncritical takes on the concept of ‘creative freedom’ as an active state explicitly free from audience consideration. Given the many other research projects being presented that looked at imagined audiences, ad hoc audiences, that explored some of Bourdieu’s theories on how culture operates as an audience context for work created within that culture, and the 50 year history of reception studies acknowledging that even in broadcast media, the audience reception of a piece is an aspect of its production (creating a feedback loop), the uncritical lean towards the concept of artistic freedom seems particularly odd.

All the more so because it is utterly central to what I do to consider my audience and their relationship with the work, with the context within which the work is produced, even seeing our community of makers and listeners as ‘the work’. I have pretty much no interest in ‘purity‘ as an artistic aim, and even authenticity I interpret in an Erving Goffmann sense, to be about consistency of messaging and intent across different ‘presentations of self‘ rather than as relating to some fixed notion of creative agency.

All the more so because it is utterly central to what I do to consider my audience and their relationship with the work, with the context within which the work is produced, even seeing our community of makers and listeners as ‘the work’. I have pretty much no interest in ‘purity‘ as an artistic aim, and even authenticity I interpret in an Erving Goffmann sense, to be about consistency of messaging and intent across different ‘presentations of self‘ rather than as relating to some fixed notion of creative agency.

Because, of course, I have by the standards of contemporary music making, a ridiculous amount of creative autonomy – I have no label, no manager, no band, no commissioner, no funding body, no institution… I’ve built a set of tools and skills over the last 30 or so years explicitly designed to get to the point where I have the absolute minimum marginal cost for music making. I get to do whatever it is that I feel is interesting and worthwhile in my creative life. So when I started on the path to funding that journey through a subscription, it was with the explicit intention of becoming MORE accountable and visible to my audience rather than more independent of them. There is now a community of people numbering only a few hundred who are collectively responsible for the financial viability of my current work mode, but who are also the social context for me understanding what it is that I’m up to. Because, as anyone who has spent any time attempting to uncritically discuss intention with musicians will know, musicians with any degree of success are mostly terrible at articulating the honest/real/material/social context for how and why they do what they do. I have so many dear friends whose explanation of their process, aims, career and relationship with the culture and economy that they operate in bears zero relationship to anything you could actually measure.

As an avid reader of the music press from the age of about 11 – starting with Smash Hits and Number One, and moving through Kerrang and Metal Hammer, then onto the NME, Melody Maker and Sounds, and eventually to glossies like Q and Vox and Word before finally ending up with online magazines and blogs, I’ve always been fascinated by the importance of wilfully delusional thinking in the self-mythologising of musicians (and of course, the enabling role that the press have played in rewarding the sensational, rarely if ever offering any kind of meaningful behavioural critique of rock excess, and building an economic model for themselves that relies on the amoral documentary work of celebrating sociopaths as iconoclasts). Indeed, that self-mythology often exists to justify (to themselves and the reader) their abhorrent behaviour towards fans and peers, but it also serves a less dystopian purpose in creating a space in which their own mythology can feed into work that desires for itself an absence of doubt and an abundance of self-confidence. It is, after all, pretty much impossible to apologetically play an arena or stadium show (perhaps providing one explanation for the prevalence of cocaine use amongst creatives, as a counter to self-doubt in an environment that eviscerates the doubtful). Even the glorious self-effacing asides of performers as engaging as James Taylor or Paul Simon rely on the reality that here is an audience made of thousands of people willing to spend significant chunks of money to hear this incredible band of musicians. There’s almost nothing to be won or proved, just a glorious legacy to be confirmed.

So what happens when your musical journey requires an ongoing dialectic of instability, questioning and perpetual forward motion on one side and a community of support and informed care on the other? How does that marry with the quite specific economies of scale that define the relationship between music as a product that accrues nostalgic magnetism over time through repeat exposure and the larger performance contexts within which it resides? Can we move beyond those growth/scale metrics of success to see the audience as the community vessel within which the work exists? In the same way that U2 or Coldplay songs can sometimes sound ridiculous robbed of the sense of meaning that 80,000 people singing along can lend to even the most banal of sentiments, is it possible to create work that only makes sense within a community invested in being the embodied vessel for the work?

The level of listener engagement required to make sense of my recorded output is at odds with both a commercial recording-as-product-to-be-marketed understanding of what recordings are ‘for‘ but also with the idea that I should have a group of expert peers who should tell me whether or not what I’m doing is significant within its elite field. I mean, I DO have those reactions – I have a commentary going back 20 years from experts in the field saying nice things about what I do and how I do it, and it would be wholly spurious to attempt to downplay the significance of press and radio coverage, or the endorsement of musicians like Victor Wooten or Michael Manring or Danny Thompson – but that’s not the ongoing purpose of the work. I rarely send any of those people or media entities links to my new work. They have the same invitation as anyone else at this point to engage with the subscription for what it is if the work, the story of the work and the broad idea of the work and its processes and contexts has meaning to them beyond a request for a quote that I can use to perhaps validate the experience of another listener who likes what they’ve heard but in the parlance of High Fidelity, isn’t quite sure if they should…

The level of listener engagement required to make sense of my recorded output is at odds with both a commercial recording-as-product-to-be-marketed understanding of what recordings are ‘for‘ but also with the idea that I should have a group of expert peers who should tell me whether or not what I’m doing is significant within its elite field. I mean, I DO have those reactions – I have a commentary going back 20 years from experts in the field saying nice things about what I do and how I do it, and it would be wholly spurious to attempt to downplay the significance of press and radio coverage, or the endorsement of musicians like Victor Wooten or Michael Manring or Danny Thompson – but that’s not the ongoing purpose of the work. I rarely send any of those people or media entities links to my new work. They have the same invitation as anyone else at this point to engage with the subscription for what it is if the work, the story of the work and the broad idea of the work and its processes and contexts has meaning to them beyond a request for a quote that I can use to perhaps validate the experience of another listener who likes what they’ve heard but in the parlance of High Fidelity, isn’t quite sure if they should…

So, my subscribers are deeply and utterly integral to the work. Our relationship is in one very real way ‘the work’ in its entirety. The recordings are a documentary process, a soundtrack to a community who either listen to recordings from afar, or show up for a set of sparsely attended but intensely enjoyable and communal gigs. The recordings are, by sheer virtue of the increasingly unknowable volume of the back catalogue, an unfolding narrative comprised of episodes rather than being best experienced as a series of products designed to build on the commercial success of the previous one and relate to the changes in culture and media in an explicit way.

It’s closer – perhaps – to a steady state economic model for music making, in that there’s a very low bar for economic viability (the project is viable at this level with 230-ish subscribers, and would be entirely sustaining of my family’s economics at around 1000 annual subscribers), and that is both a hindrance to growth (in that the point of economic engagement – and access to the vast majority of the catalogue – is your first year’s subscription fee of £30) but also is (in Bourdieu’s formulation) a position taken in opposition to the prevailing quest for an ever expanding streaming listenership, where 250,000 people contributing fractions of a penny per listen each is the aim. There is an affordance within that model for a specific kind of creative-economic aspiration, and it’s not one that favours the kind of thought process, time scale, work/life balance or narrative context that interests me as a creative person.

It’s closer – perhaps – to a steady state economic model for music making, in that there’s a very low bar for economic viability (the project is viable at this level with 230-ish subscribers, and would be entirely sustaining of my family’s economics at around 1000 annual subscribers), and that is both a hindrance to growth (in that the point of economic engagement – and access to the vast majority of the catalogue – is your first year’s subscription fee of £30) but also is (in Bourdieu’s formulation) a position taken in opposition to the prevailing quest for an ever expanding streaming listenership, where 250,000 people contributing fractions of a penny per listen each is the aim. There is an affordance within that model for a specific kind of creative-economic aspiration, and it’s not one that favours the kind of thought process, time scale, work/life balance or narrative context that interests me as a creative person.

Given that ‘creative freedom’ is a mostly nonsensical formulation acknowledging the complexity of influences that we’re all consciously and unconsciously subjected to every time we even think about music let alone engage with activities around making it and learning how to make it, I’m happy to hitch my music waggon to a community model that brings with it an affordance for a more reflective mode of music making, and a more episodic, decommoditised context for the releasing of recordings. It’s not like the subscription itself isn’t still a ‘product’ or commodity – it has a price and with that price comes a perception of the value of the offering in relation to that price, but what’s beyond that as an experience both live and recorded is what my PhD is all about… I’m currently about 18 months behind where I should be with written evidence of what I’m up to, but the thinking (and non-official writing) part is pretty well developed. Hopefully there’ll be a bunch more shows for y’all to come to in the very near future…

Given that ‘creative freedom’ is a mostly nonsensical formulation acknowledging the complexity of influences that we’re all consciously and unconsciously subjected to every time we even think about music let alone engage with activities around making it and learning how to make it, I’m happy to hitch my music waggon to a community model that brings with it an affordance for a more reflective mode of music making, and a more episodic, decommoditised context for the releasing of recordings. It’s not like the subscription itself isn’t still a ‘product’ or commodity – it has a price and with that price comes a perception of the value of the offering in relation to that price, but what’s beyond that as an experience both live and recorded is what my PhD is all about… I’m currently about 18 months behind where I should be with written evidence of what I’m up to, but the thinking (and non-official writing) part is pretty well developed. Hopefully there’ll be a bunch more shows for y’all to come to in the very near future…

Anyway, the one open-ended question at the end of this is directed at current, former and perhaps even future subscribers – how does that lot map to your experience of being a subscriber? Is it just an economically meaningful way to get a bunch of music that you can’t get elsewhere, or is there more to it? Answers in the comments please 😉