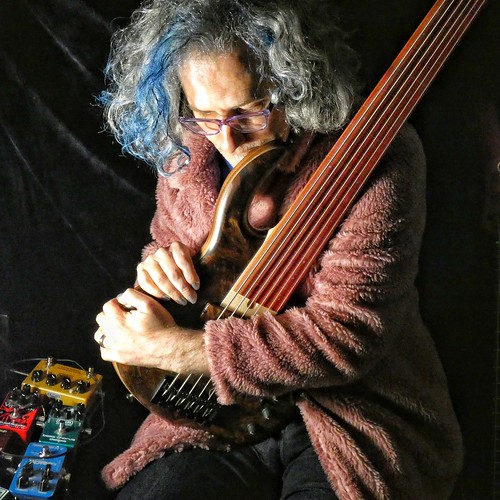

Today’s influential collaborator is BJ Cole, and for someone who changed my music-life as much as BJ did, there’s precious little documentation of us playing together. This is because the vast majority of the development that happened for me while playing with BJ happened in my living room. For a couple of years we got together as often as possible to just play. Sometimes it was every other week. When we were busy, our sessions were a little more spread out. But it was time and space to experiment with a particular kind of abstract textural improv that was utterly formative for me. BJ was quite involved with the London Improvisors Orchestra at the time, which gave him space to apply his mind-bendingly broad approach to the pedal steel guitar to some pretty out music. He was also working with Luke Vibert and others on the EDM scene, so his development of his own voice was an extraordinary thing to witness – especially in a musician who was already the most influential practitioner of his instrument that this country has ever produced (for those who don’t know, BJ played the pedal steel part on Tiny Dancer by Elton John, and played with David Sylvian, Robert Plant, Bjork, Deacon Blue, Paul Young, REM, Beck, and was in the Verve, as well as making groundbreaking ambient records under his own name).

Today’s influential collaborator is BJ Cole, and for someone who changed my music-life as much as BJ did, there’s precious little documentation of us playing together. This is because the vast majority of the development that happened for me while playing with BJ happened in my living room. For a couple of years we got together as often as possible to just play. Sometimes it was every other week. When we were busy, our sessions were a little more spread out. But it was time and space to experiment with a particular kind of abstract textural improv that was utterly formative for me. BJ was quite involved with the London Improvisors Orchestra at the time, which gave him space to apply his mind-bendingly broad approach to the pedal steel guitar to some pretty out music. He was also working with Luke Vibert and others on the EDM scene, so his development of his own voice was an extraordinary thing to witness – especially in a musician who was already the most influential practitioner of his instrument that this country has ever produced (for those who don’t know, BJ played the pedal steel part on Tiny Dancer by Elton John, and played with David Sylvian, Robert Plant, Bjork, Deacon Blue, Paul Young, REM, Beck, and was in the Verve, as well as making groundbreaking ambient records under his own name).

Our experimental sessions in my living room were space to push ideas to breaking point – BJ had a Gibson Echoplex, and I had my Looperlative (or probably a pair of EDPs when we first started playing together) so we could create a massive layered sound – we built, and the dismantled, a whole load of cinematic and occasionally terrifying soundscapes. The great thing about it for me was that, because we had a tendency to occupy similar sonic territory (the steel has a huge range, and as I was using the eBow an awful lot at the time, we were both producing a lot of sustained chords in similar registers) I had to listen more intently than ever to try and find the space where our sound-worlds met. Often in those sessions things would go off the deep end, and we’d end up with harsh noise (I wonder if any of that music is on a hard drive somewhere? We did record a lot of it…) It was a project that involved a lot of trial and error, a lot of rescuing of improvisations that got away from us.

Our experimental sessions in my living room were space to push ideas to breaking point – BJ had a Gibson Echoplex, and I had my Looperlative (or probably a pair of EDPs when we first started playing together) so we could create a massive layered sound – we built, and the dismantled, a whole load of cinematic and occasionally terrifying soundscapes. The great thing about it for me was that, because we had a tendency to occupy similar sonic territory (the steel has a huge range, and as I was using the eBow an awful lot at the time, we were both producing a lot of sustained chords in similar registers) I had to listen more intently than ever to try and find the space where our sound-worlds met. Often in those sessions things would go off the deep end, and we’d end up with harsh noise (I wonder if any of that music is on a hard drive somewhere? We did record a lot of it…) It was a project that involved a lot of trial and error, a lot of rescuing of improvisations that got away from us.

The thing that I think made it most interesting for me was how successful the music was whenever we played live. Those safe-sessions in my house allowed us to push boundaries that meant that when we played live, we had a whole load of experience to fall back on, and were less apt to fall over the cliff-edge. Allowing yourself to find what happens when things get too messy, or when sounds pile up to the point where it begins to lose meaning – those are important and formative experiments. I’m deeply grateful to BJ for all the time we spent finding sounds and ideas, pushing things too far, and then applying it to a range of gigs in different combinations – my favourite of our projects was a trio with Cleveland Watkiss. We played a number of times at my night, The Recycle Collective, and it was an amazing experience and a great combinations of sounds. But I also loved opening for and sitting in with BJ’s group at the time, with Eddie Sayer on percussion and Ben Bayliss on laptop, playing the music from his brilliant Trouble In Paradise album.

The thing that I think made it most interesting for me was how successful the music was whenever we played live. Those safe-sessions in my house allowed us to push boundaries that meant that when we played live, we had a whole load of experience to fall back on, and were less apt to fall over the cliff-edge. Allowing yourself to find what happens when things get too messy, or when sounds pile up to the point where it begins to lose meaning – those are important and formative experiments. I’m deeply grateful to BJ for all the time we spent finding sounds and ideas, pushing things too far, and then applying it to a range of gigs in different combinations – my favourite of our projects was a trio with Cleveland Watkiss. We played a number of times at my night, The Recycle Collective, and it was an amazing experience and a great combinations of sounds. But I also loved opening for and sitting in with BJ’s group at the time, with Eddie Sayer on percussion and Ben Bayliss on laptop, playing the music from his brilliant Trouble In Paradise album.

It was such a privilege to get to play with a musician of BJ’s stature, but moreso a musician of his deep, ceaseless commitment to moving forward in his own creative path. I learned as much just from the experience of playing with someone who was already ‘a legend’ in the pop world, already absolutely at the top of his game, but who never stopped reaching for new things, who was ceaselessly curious about what else he might be able to do with his instrument. I carry that inspiration with me every time I pick up the instrument, and I really hope we get to play together again soon. It’s been way, way too long.