There’s a scene at the end of the film Walk Hard, where Dewey Cox plays his last ever show. It’s a weirdly moving scene, though still ridiculous in keeping with the rest of the film. In the wings are the spirits of many of the people who had died during the life story we’ve just witnessed in the rest of the film. Significant figures from his journey there to cheer him at this momentous moment.

I’ve finally got my PhD. Done and dusted. Come in, Dr Steve. I passed my viva in January, but it was with ‘substantive corrections’. At first I was irritated at the requests, concerned that the required additional sections would upset the symmetry of the whole thing. But by giving it time and committing to the vision for it that my examiners saw, I’ve ended up with a much stronger thesis.

PhDs are always, always a big f’ing deal. The normal time frame is 3 years full time or 5 years part time. Mine was extended dramatically beyond that, first by a suspension during COVID, and then again for cancer and recovery. So from enrolment to graduation is just shy of ten years. TEN YEARS. I was 42 when I started this. Flapjack was 5. It was pre-Brexit, pre-COVID, pre-cancer, pre-divorce. So much in my life has changed in those ten years, and now this chapter is finally closed. An invitation to look forwards.

I’m deeply, deeply proud of the work. It feels like a really significant document of a 25 year journey to build a very unusual form of community around my music, one that as the thesis shows, was kind of there in spirit from the start.

But in writing it, and in thinking about it now, I’m deeply, immeasurably indebted to so many people for their impact on the work. My supervisors, Dr Paul Thompson and Dr Bob Davis, were brilliant. Infuriating and annoying at times, of course, as they should be, but they guided me towards this, and it wouldn’t be what it is without them. And then I had the people who would advise me as I went along. Dr Jon Greenaway, AKA The LitCritGuy read through my ‘confirmation of registration’ at the end of my first year, and really, really helped me get that together. Dr Annette Markham spent hours and hours with me on Zoom helping me make sense of method, expanding my vision for how to be rigorous about documenting a community and its interactions, but also just being super interested in and excited about what I was up to at a point where I was sometimes unsure of even what it was. What an absurd luxury to have such extraordinary people helping me out. Reading their books and work online was inspiring enough, but the support as friends and advisors was priceless.

And then we arrive at the Walk Hard film clip. Because others who shaped the work in vital, transformative ways, who encouraged, advised, supported and cajoled me, are no longer with us.

First to help shape the PhD was Dr Phil Tagg. We met at a mini-conference at Leeds Beckett before I started the PhD, at which he said my questions to him after he’d presented were ‘the hardest I’ve been grilled since my viva’. Phil was a mercurial and unique scholar, a long-winded, cantankerous, meandering writer who through that process uncovered some extraordinary insights about music and semiotics. When I went to Leeds to discuss the topic of my PhD I had an hour with Phil and he told me how boring every idea I had was until I started talking about the audience. Then he got excited. His lack of bullshit meant that he waited until something seemed worthwhile to affirm it. I desperately needed that and was looking forward to him being my antagonist during my studies. But it was the last time I saw him. He dissappeared off to Canada and died last year…

The first to leave was Neale Bairstow. Neale’s contribution to the work could’ve been its own PhD – from his hospital bed in France, Neale, who I never met, wrote eight pages about how he understood what was going on between me, my music and my audience. He understood what this PhD was about WAY WAY before I did. I didn’t prompt him, we didn’t discuss it beforehand, he just wrote it and got it. And holy shit did he get it. And then he died. Before I could tell him just how heavily his work impacted my work. I only really incorporated it into the PhD in the last year of writing it. Such was the depth and breadth of his insight that it took me that long to see that what I was trying to understand was what he’d explained back then.

And then there was Dr John Hinks, who I knew first and fullest as a student of mine. Teaching John bass was one of the great joys of my teaching life. He was full of adventure, enthusiasm and curiosity, and with a little encouragement became a prolific improviser, working with groups in his home town of Leicester and also here in Birmingham. His great contribution to the PhD was encapsulated in one conversation, recounted in the work. After an improvised gig at Tower Of Song, featuring a duo of me and trumpet genius Bryan Corbett, I asked John what he thought of it, and he said ‘I don’t know, I’ll tell you when I’ve heard it again’. It was a proper thunderbolt moment for me, realising what the subscription offers to people at gigs, in the knowledge that what they’ve just witnessed being created before their eyes and ears will come back to them as a recording. John died almost exactly a year ago, unexpectedly. He leaves a huge hole, and I’ll forever miss his friendship.

My other Zoom advisor during COVID was Dr Jonathan Sterne. We’d met online in the late 90s, on a bass player mailing list that’s written about in my Thesis. Reconnecting years later in Oxford, we became online friends, and our Zoom chats were alternately PhD support and bass lesson. We skill swapped and talked endlessly. When Jonathan died at the start of the year, I copied our Facebook chat into a text document and it was as long as my Thesis. His advice, his kindness and patience with my often not having any real clue what I was doing, was otherworldly. Jonathan is a scholar who defined the field of Sound Studies, a scholar of monumental significance, and here he was helping me make sense of my ramblings and telling me over and over again how important the work was, messaging me every time he would quote me in a lecture (mostly my extensive rants about how dreadful Spotify is!)

And finally Dr Emily Baker-Abis. Without doubt one of the greatest singer/songwriters I’ve ever encountered, Emily was also a razor sharp academic, a theorist and observer who made sense of so many things. Our PhD study periods overlapped, so we would occasionally motivate one another with swapping bits of writing, 500 words at a time. She was encouraging and critical and insightful and brilliant in equal measure, never letting me get away with stuff that could be written better. She’d ask questions that sometimes were hugely encouraging because I’d already answered them further on in the section than the 500 words I’d sent her. And if I was thinking like Emily, that was a good thing, right? When she was diagnosed with cancer at the start of the year, we chatted about it, and made plans for more collaborative writing and work together. We won’t get to do it.

So now, at the end of the Beautiful Ride of this PhD, I’m looking to my left and right, and there they are, Jonathan, Emily, John, Neale and Phil. The great cloud of witnesses, cheering me on. They are woven deep into the work, and collectively, I’m pretty sure I may not have even finished it without them.

And I’m now Dr Steve. Ten years. Holy shit. It’s finally done. Let’s see what’s next.

Weird thing I just remembered. I once did a voice-over job for Microsoft – about 20 years ago. I can’t remember what the product was, but I remember that the opening line of the script was “Why do we teach? To change the world one student at a time”, and despite that being cheesy MS marketing copy, it still holds true.

Weird thing I just remembered. I once did a voice-over job for Microsoft – about 20 years ago. I can’t remember what the product was, but I remember that the opening line of the script was “Why do we teach? To change the world one student at a time”, and despite that being cheesy MS marketing copy, it still holds true.

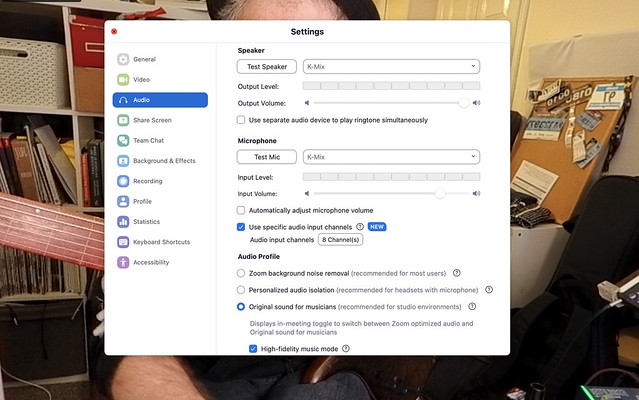

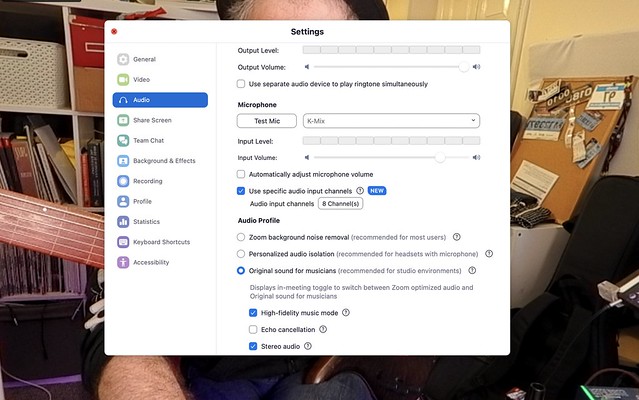

Heading into the COVID lockdown and everything moved online. I wrote tutorials for other teachers and performers in how to set up for streaming lessons and gigs, and got on with moving all my bass teaching online.

Heading into the COVID lockdown and everything moved online. I wrote tutorials for other teachers and performers in how to set up for streaming lessons and gigs, and got on with moving all my bass teaching online. I am adamant that it is not my job to decide the exact path every student should go on. My students are almost exclusively grown-ass adults with a lifetime’s experience as music listeners, and generally some familiarity with the instrument (I love teaching total beginners, but it doesn’t happen very often). My task is to equip them to play the music that inspires and motivates them, to plot a journey towards their own creative aspirations and intentions. For some of them that’s playing bass in a band in a particular genre. For others it’s about broadening their general skill set regarding navigating the fretboard in terms of keys and melodic/intervallic patterns. For some it’s developing a practice towards building a vocabulary for improvisation, and still others it’s playing solo. I don’t decide what they should want to do, I just give them the tools to get there. And in any given week, I give them WAY more tools than they need, because I can, and because while rewatching the video there might be one section that really connects with them that they can watch over and over again and really dig into. They also have a document of their own playing that can be really useful for reflective and reflexive assessment of where they are up to.

I am adamant that it is not my job to decide the exact path every student should go on. My students are almost exclusively grown-ass adults with a lifetime’s experience as music listeners, and generally some familiarity with the instrument (I love teaching total beginners, but it doesn’t happen very often). My task is to equip them to play the music that inspires and motivates them, to plot a journey towards their own creative aspirations and intentions. For some of them that’s playing bass in a band in a particular genre. For others it’s about broadening their general skill set regarding navigating the fretboard in terms of keys and melodic/intervallic patterns. For some it’s developing a practice towards building a vocabulary for improvisation, and still others it’s playing solo. I don’t decide what they should want to do, I just give them the tools to get there. And in any given week, I give them WAY more tools than they need, because I can, and because while rewatching the video there might be one section that really connects with them that they can watch over and over again and really dig into. They also have a document of their own playing that can be really useful for reflective and reflexive assessment of where they are up to.